2014 Museum Dedication Remarks

Oct 13th, 2018 by admin

Current Chair of the Museum Committee, the Very Reverend Dr. John Wm. Houghton, made these comments on the opening of the Museum’s new space on June 14, 2014. Fr. Houghton was introduced by the then-Chair, Mr. George Duncan.

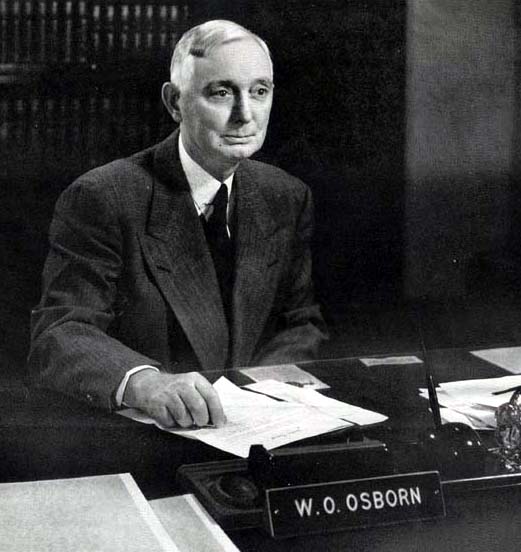

Thank you, George, and my thanks as well to all of the people who have worked so hard to bring our museum into its new life here on this historic corner of “Osborn Square.” I think that that old name for this block may still officially be on the record books, and if it isn’t, it probably should be: W. O. Osborn was surely one of the big people of our little town, one who ought not to be forgotten, and it is altogether fitting that our reborn museum should have its place in what was once his office.

In fact, Mr. Osborn—my elders may have called him “W. O.,” “Will” or even, in his absence, “Uncle Billy,” but I certainly never thought of him so informally—Mr. Osborn illustrates one of the points of Culver’s history, which is simply that that history isn’t really very long. Born in 1885, Mr. Osborn took a place, in 1906, in his father-in-law’s bank (which had originally been founded by his own father, John Osborn) and was then called to the bar in 1912. He served as attorney for my great-grandfather, another William, during the 1919 trial over my twice-great-grandfather Thomas’s estate, and sitting right there in that office Mr. Osborn was able to tell me in detail not only about Thomas’s character but even about his dental work, which turned out to have some bearing on the trial. And here’s the thing: that Thomas, the one Mr. Osborn was telling me about, was one of the pioneers of 1836—he was only a seven year old boy, admittedly, and he lived to be 89, and Mr. Osborn himself was nearly 90 when he talked with me. Nonetheless: the man whose office now becomes our museum knew and spoke with and remembered the pioneers; he knew people who entertained Chief Menominee in their homes. Our beginnings are that close. [Photo of Mr. Osborn in 1948]

in 1885, Mr. Osborn took a place, in 1906, in his father-in-law’s bank (which had originally been founded by his own father, John Osborn) and was then called to the bar in 1912. He served as attorney for my great-grandfather, another William, during the 1919 trial over my twice-great-grandfather Thomas’s estate, and sitting right there in that office Mr. Osborn was able to tell me in detail not only about Thomas’s character but even about his dental work, which turned out to have some bearing on the trial. And here’s the thing: that Thomas, the one Mr. Osborn was telling me about, was one of the pioneers of 1836—he was only a seven year old boy, admittedly, and he lived to be 89, and Mr. Osborn himself was nearly 90 when he talked with me. Nonetheless: the man whose office now becomes our museum knew and spoke with and remembered the pioneers; he knew people who entertained Chief Menominee in their homes. Our beginnings are that close. [Photo of Mr. Osborn in 1948]

Our beginnings are close: to put it into numbers, the beginning is 170 years and six days ago: it was on June 8 of 1844 that the 22-year-old Bayless Lewis Dickson platted Uniontown in the southwest corner of the southern forty acres of his 150 acre homestead. We would have expected the property to be 160 acres, a quarter of a square mile, but the lake nibbles ten acres out of the eastern edge. The western edge, though, runs straight as a ruler, now just as it did then: it’s the line of the alley just off there behind you, the one that becomes School Street. But the beginning of our history is more than just the story of my cousin Bayless’s little plat. We could look for its beginning all the way back to the time in the late 1700s when the Potawatomi began to move into this area, driving the Miami and Fox further south; or we could look to the tiny British farms, crushed by rural poverty in the years after the Napoleonic wars, from which many of the pioneers emigrated; we could look to Bayless Dickson’s nephew, Daniel McDonald, who thought the north bluff of the lake, just outside of town, would be a good location for a clubhouse, a place to get away from the hustle and bustle of Plymouth; we could look to Kewanna, where A. D. Toner decided that as long as he was buying lakeside property for the Vandalia Railroad he might as well buy some more for himself, extending the town eastward toward McDonald’s clubhouse; or we could look north-east, over to the vanished village of Wolf Creek, once home to the Zehner Mill and the Hand family farm—we could look there not only because William Hand’s grocery store used to stand where our Heritage Park is, but also because

Wolf Creek is where William’s sister Emily Jane (known in the family as “Jennie”) fell in love with a traveling stove salesman and, on September 1, 1864, married him, becoming Mrs. Henry Harrison Culver, with significant implications for our town. [The Hand store at 103 S. Main Street is the building with the porch in this photo.]

It’s a strong urge, and a valid one, to know these beginnings: in one sense, we can’t find our bearings without them. That’s not to say, of course, that simply knowing what the situation was for our ancestors at some given point in history will allow us to extrapolate into their future without the application of our twenty-twenty hindsight. Consider Marmont, for example. I have a Pennsylvania vanity plate on my car with that name on it, and when I first applied for the plate, someone in the state capital at Harrisburg sent the application back, demanding to know what “Marmont” meant. I sent them a printout of the Wikipedia page about Auguste Frédéric Louis Viesse de Marmont, Duc de Ragusa, who was, at the end of March of 1814, the last of Napoleon’s marshals to defect from Bonaparte to the royalist cause.  Sometime around 1857, Bayless Dickson’s brother-in-law, Thomas K. Houghton (not my ancestor with the bad teeth, but his cousin), changed the name of the town, at the request of one of its citizens, to Marmont, in honor of the Marshal, who had died in 1852. Back in 1814, Marmont had insured the restoration of Louis XVIII, of the House of Bourbon—a legitimately big deal, perhaps even a big enough deal to warrant naming the town after him; but surely even Marmont’s most devoted fans here in Indiana in the 1850s could not have anticipated that, in the 1970s, the children of a Bourbon princess, the King of Spain’s older sister, would actually spend their summers at Mr. Culver’s camps. Knowing history will not, by itself, allow us to predict the future: but then again nothing else will, either. [Portrait of Marmont by Jean-Baptiste Paulin Guérin [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons]

Sometime around 1857, Bayless Dickson’s brother-in-law, Thomas K. Houghton (not my ancestor with the bad teeth, but his cousin), changed the name of the town, at the request of one of its citizens, to Marmont, in honor of the Marshal, who had died in 1852. Back in 1814, Marmont had insured the restoration of Louis XVIII, of the House of Bourbon—a legitimately big deal, perhaps even a big enough deal to warrant naming the town after him; but surely even Marmont’s most devoted fans here in Indiana in the 1850s could not have anticipated that, in the 1970s, the children of a Bourbon princess, the King of Spain’s older sister, would actually spend their summers at Mr. Culver’s camps. Knowing history will not, by itself, allow us to predict the future: but then again nothing else will, either. [Portrait of Marmont by Jean-Baptiste Paulin Guérin [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons]

Knowing our history won’t allow us to predict the future: but not knowing our history is, surely, a prescription for disaster. At the very least, our history is where we stand—it is the body of stories we tell about ourselves to define who we are: and this re-created museum is a repository of those stories.

*

On a day like this, when we think of the rebirth of the museum, some people (Harry Potter fans, at the very least) will also think of the image of the mythological phoenix, born again of its own funeral pyre—though there has, thankfully, been no fire involved in this process! But the phoenix can lead us not only to an image but also, I think, in a round-about way, to a poetic theme, a theme for the day and for this project. Back in the 16th Century, Queen Elizabeth the First of England used the burning phoenix as her personal symbol; her cousin and rival, Mary Queen of Scots, adopted as her symbol her husband’s grandfather’s emblem of the salamander (not our familiar amphibian, but a creature with a phoenix-like mythology of being reborn in fire) and added, in French, the motto, “In my end is my beginning.” Finally, in the 1940’s, the poet T. S. Eliot—a St. Louis man, originally, though he was living in England by then—took Queen Mary’s motto as the theme for a poem. Eliot wrote, in part:

What we call the beginning is often the end

And to make an end is to make a beginning.

The end is where we start from. . . .

A people without history

Is not redeemed from time, for history is a pattern

Of timeless moments. . . .

We shall not cease from exploration

And the end of all our exploring

Will be to arrive where we started

And know the place for the first time. (Four Quartets, “Little Gidding”)

This place, here at the edge of Bayless Dickson’s farm, is where we began, 170 years ago—it is, in Eliot’s words, the origin of our “pattern of timeless moments”; and at the same time we dedicate a museum here today so that it can be for us, and for those who come after us, the end of all our exploring, so that we can, indeed, “arrive where we started / And know the place for the first time.”